Geometry, features, and orientation in vertebrate

animals: A pictorial review

Ken Cheng and Nora S. Newcombe

Macquarie University & Temple University

Chicks

|

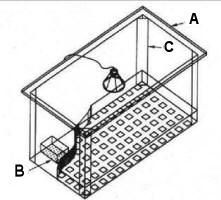

| Figure B-1: Apparatus used by Vallortigara et al., 1990. Thanks to Giorgio Vallortigara for supplying this and the following five pictures. |

Vallortigara, Zanforlin, and Pasti (1990) tested chicks in the reference memory paradigm, and found that the birds used both geometric and featural properties readily. This figure shows a schematic drawing of their rectangular test apparatus. In all the experiments, the food remained in one corner throughout training. The animals were disoriented between trials, so that they had to use cues within the arena to orient.

a: one-way glass over the top of the arena

b: food box

c: panel in the corner, used in many of the experiments from Vallortigara’s group

|

| Figure B-2: |

Examples of panels in the corner, with a chick at work on the task.

|

| Figure B-3: |

Overhead view of another test situation. The blue wall is a featural cue, the rectangular shape a geometric cue.

|

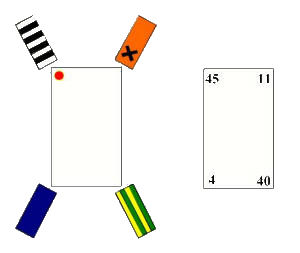

| Figure B-4: |

Overhead view of a test situation with panels in the corners serving as featural cues.

|

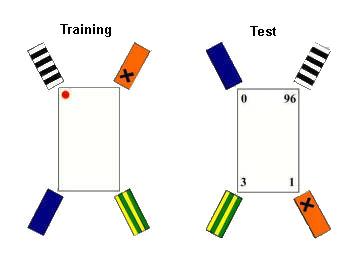

| Figure B-5: Results from Vallortigara et al., 1990. |

When features and geometry were provided (left), the chicks were mostly correct (results not shown). The chicks showed no systematic rotational errors, unlike rats, young children, and rhesus monkeys. This meant that they used featural cues.

That the chicks learned geometry as well is shown on the right, when all featural cues were removed for a test. The chicks concentrated their searching in the correct corner and the diagonal opposite, the rotational error. Without featural cues, it is in principle impossible to distinguish these two locations. Note that having the featural cues during training did not overshadow the learning of geometric cues. This is a theme found in all species tested. See the cue competition section.

|

| Figure B-6: Results of featural/configuration conflict test from Vallortigara et al., 1990. |

In this test, featural and geometric cues were put in conflict. This was done by moving the nearest feature, a beacon at the target, to a geometrically different corner on a test (right). Chicks overwhelmingly opted to ‘go with’ the beacon.

|

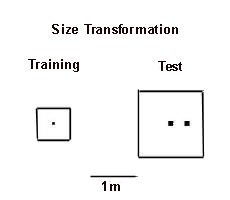

| Figure B-7: Size transformation test. |

Results of transformations of the size of the training arena came later (Tommasi, Vallortigara, & Zanforlin, 1997; Tommasi & Vallortigara, 2000). Chicks were trained to search at the center of a square space. When the square was expanded on a test, chicks showed tendencies to both search at the center and to search at the correct absolute distance from a wall. This suggests that both absolute and relative distances, two kinds of geometric cues, are encoded.

Information on the neurophysiology underlying the encoding of geometric and featural cues is given in the neurophysiological section.

|