Created by Lauren Kosseff

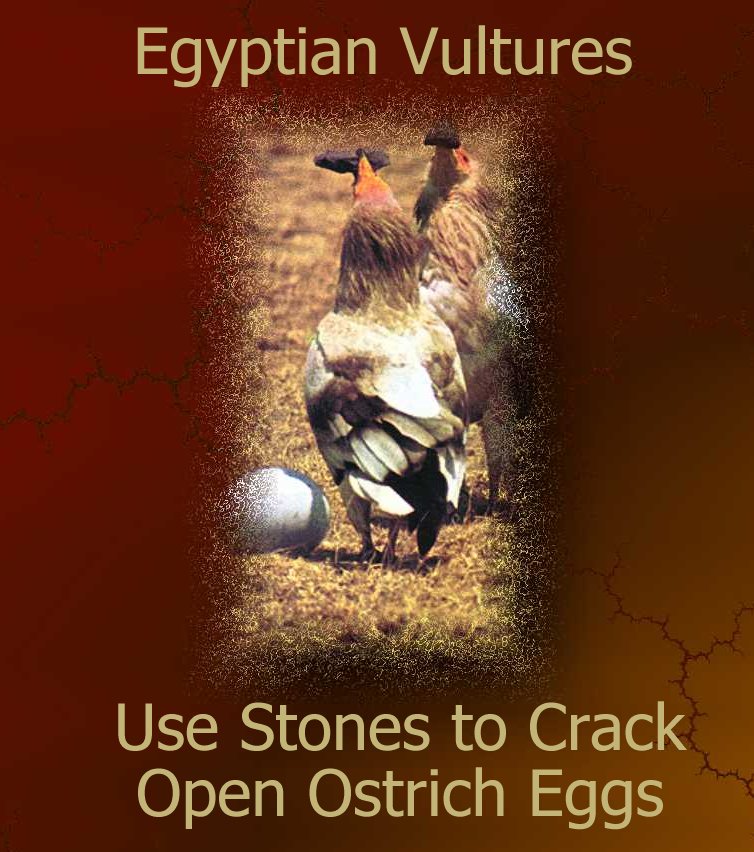

Hungry Egyptian vultures

use ingenuity in obtaining their food. Since the shells of ostrich eggs are too hard

to break open by simply pecking at them, the vultures use rocks to assist them.

According to reports by Jane Goodall from Tanzania, the vultures will search as far as 50

yards from the coveted egg in order to find a proper smashing tool. Interestingly,

the forward jerking movement of the vultures' head exhibited when breaking an egg with a

stone is very similar to the movement used when the bird simply pecks to break open an

egg. Other species of birds break eggs open by throwing them down on stones.

However, this behavior is not considered tool use because the stone is not being used as

an extension of the bird's body.

Alcock(1975) theorized that the vultures

originally threw eggs to break them open. They then evolved from throwing the eggs

to throwing rocks at the eggs. The use of rocks to break the eggs open probably

began when a vulture accidentally hit an egg with a rock. Vultures' aim in

stone-throwing is poor, hitting the target with only 40-60% of their throws. Despite

their imperfect aim, the vultures persist until they succeed in cracking the egg. A

study by C.R. Thouless in 1989 supports Alcock's theory with its finding that the vultures

prefer to use egg-shaped stones. The use of stone-shaped eggs belies a

connection to the usual behavior of throwing an egg against the ground to crack it.

An interesting study demonstrated that shape

not only dictates the tools used by vultures, but also the objects which they choose to

crack(National Geographic Society, 1972). The study showed that although vultures

will try to use a stone to break open a green or red egg-shaped decoy, they do not attempt

to open white cubes.

Observations by C.R. Thouless and his

co-workers(1989) of young vultures reared without exposure to adults proved that throwing

stones at eggs is an innate, not learned, skill. However, the vultures do need to

learn that ostrich eggs are a rewarding source of food before they begin cracking them

with rocks. Such learning occurs when a young vulture encounters an egg which has

already been cracked by another bird and tastes its contents.

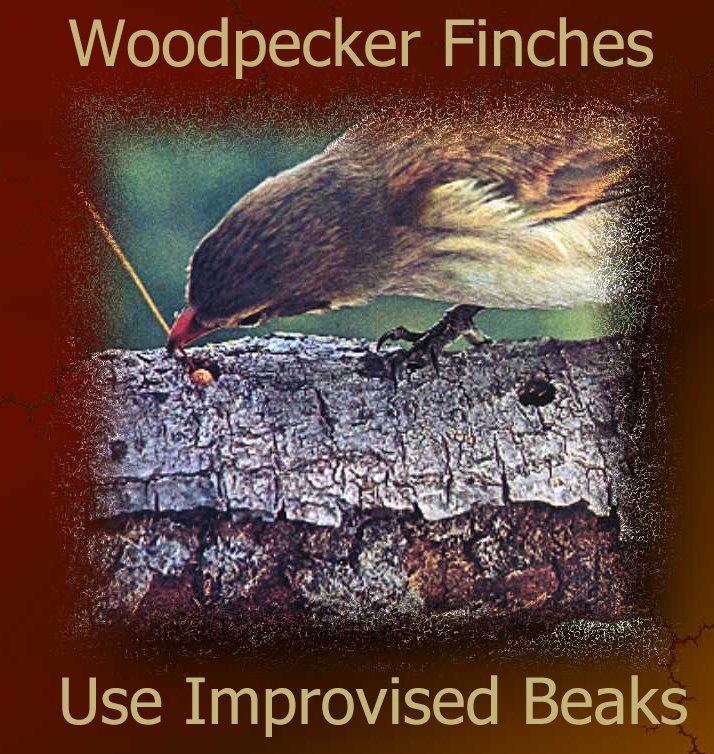

The woodpecker finch, residing on the Galapagos

islands, is the most amazing of Darwin's finches. Its talents include tool use as

well as tool fabrication. In the above photograph, the finch is prying grubs out of

a tree branch with a cactus spine. A woodpecker's long barbed tongue enables it to

extract grubs from branches without the assistance of a tool. On the other hand, the

woodpecker finch compensates for its short tongue by grasping a cactus

spine in its beak and prying grubs out of the branch with the cactus spine. The

finch then drops the cactus spine and holds it under its foot while eating the grub.

The cactus spine is carried from branch to branch for reuse.

Observations by Millikan and Bowman(1967)

reveal that the finches adjust their posture and manipulation of the tool according to its

size and shape. They also discovered that the woodpecker finches were more likely to

seek out and use tools with an increase in hunger level. Milikan and Bowman also

conducted a study in which a different species of finch from the Galapagos islands, the

large-cactus ground finch, was caged next to a group of woodpecker finches. Although

the large-cactus ground finches do not use tools to probe for grubs in their natural

environment, they acquired similar tool usage to the woodpecker finch when caged in such

close proximity. Other species of finches, however, did not learn to use tools as

probes when they were caged next to the woodpecker finch.

A researcher was fortunate enough to observe a

young woodpecker finch's acquisition of the skill of using the cactus spine. The

finch began by attempting to obtain grubs from a tree branch simply by using its beak.

When that system frequently failed, the finch implemented a twig in order to reach

further into the branch. Another finch was observed snapping off a part of a forked

twig in order to fashion a superior tool. Millikan and Bowman(1967) also observed

woodpecker finches shortening long cactus spines in order to form more manageable tools.

This manipulation of an object for tool use is particularly impressive.

Brown(1975) posits that woodpecker finches

would be replaced by woodpeckers or nuthatches if either of those species were to come to

the Galapagos islands. His basis for this theory is that woodpeckers and nuthatches

have more effective morphological means for accomplishing what the woodpecker finch does

with tools.

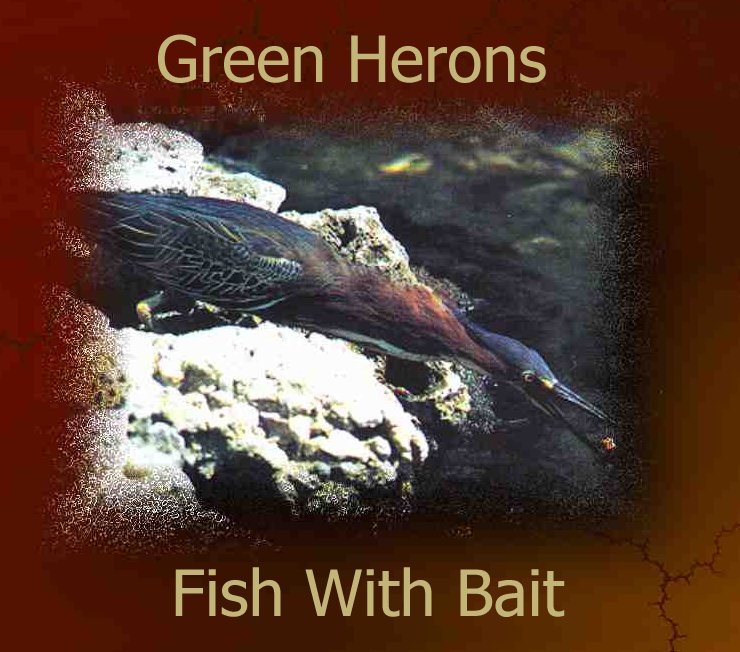

The green

heron drops a small object onto the surface of the water. Fish swim to the surface,

hoping that the object might be prey. The heron then snatches the unsuspecting fish

which come along to inspect its bait.

The practice of bait-fishing is

rare among green herons. The fact that few herons use bait-fishing indicates that it

is not an innate behavior. Moreover, the infrequency of bait-fishing suggests that

the behavior is not culturally transmitted. The roots of using objects to attract

fish are unclear. One theory suggests that herons are imitating human behavior when

they use bait for fishing. However, the fact that attempts to teach herons to use

bait for fishing have failed suggest otherwise.

Another possibility is that

herons learn to use bait for fishing through experience, i.e. the heron accidentally drops

an object in the water and sees the object's attraction to fish. Some researchers

believe that making the connection between dropping something on the water and seeing the

crowd of fish that results and intentionally dropping bait into the water is very

difficult. According to these researchers, only the exceptionally intelligent herons

acquire the skill of bait fishing. The intelligence requirement accounts for the

small percentage of green herons who engage in bait-fishing. Other researchers argue

that the reason for the infrequency of the behavior is that few herons actually have the

opportunity to observe the results of dropping an object into the water.

|