|

|

Excerpted from C. L. Morgan's book The Animal Mind  In the north

of England competitions are not uncommon where, say, three sheep have to be driven over a

definite course, between certain posts and round others, through narrow passages and into

a small ‘fold’- all within a certain time limit. At such a competition success

depends on two things; first, the training of the dog to respond at once, say, to some six

or eight whistle signals, often accompanied by gestures; and secondly, the judgement of

the shepherd. The signals with different inflections have for the dog meaning, such as

drive straight on, from this side, from that, stop, lie down, creep forward, and so forth.

The dog’s whole business is to obey these signals. And the instant response of a

well-trained dog is admirable. But throughout he is merely the executant of his

master’s orders. He originates no important step. And if you listen to the criticisms

of the other shepherd during a competition you will find that they are mainly passed on

the judgement shown by the master, and only, in palpable failures in obedience, on the

behavior of the dog. The intelligent animal is what he is trained to be – one whose

natural powers are under the complete control of his master, with whom the whole plan of

action lies. In the north

of England competitions are not uncommon where, say, three sheep have to be driven over a

definite course, between certain posts and round others, through narrow passages and into

a small ‘fold’- all within a certain time limit. At such a competition success

depends on two things; first, the training of the dog to respond at once, say, to some six

or eight whistle signals, often accompanied by gestures; and secondly, the judgement of

the shepherd. The signals with different inflections have for the dog meaning, such as

drive straight on, from this side, from that, stop, lie down, creep forward, and so forth.

The dog’s whole business is to obey these signals. And the instant response of a

well-trained dog is admirable. But throughout he is merely the executant of his

master’s orders. He originates no important step. And if you listen to the criticisms

of the other shepherd during a competition you will find that they are mainly passed on

the judgement shown by the master, and only, in palpable failures in obedience, on the

behavior of the dog. The intelligent animal is what he is trained to be – one whose

natural powers are under the complete control of his master, with whom the whole plan of

action lies.

In criticism of this statement I should now say that it seems to imply that there was no plan in the dog’s mind, whereas the more cautious inference is that, for success from the masters point of view, and to attain his end in view, the dog’s plan must be subordinate to his plan. That, however, is not the point. The point now is that the trainer get some insight into what, as he believes, goes on the dog’s mind, not on one occasion only but during a long series of occasions. But since the shepherd is presumably not a trained psychologist, he bases what he tells us on commonsense belief as to the nature of the dog’s mind. Let us now introduce the psychologist in some measure trained to the task of interpreting mental processes. He starts with some instance of behavior, preferably observed by himself, and tries to get behind it so as to tell us what, as he believes, goes on in the mind of the animal. The way in which my dog learnt to lift the latch of the

garden gate and thus let himself out was on this wise. The iron Here again I might now express my interpretation more cautiously. What I wish to stand out is this: that in some sense of the words Tony had, as I believe, an end in view, or ‘objective,’ namely to get out into the road; but that he had not at the outset, before gazing out there, there and elsewhere, discovered the means by which this end in view could be attained. Now the outcome of the completed behavior, lifting the latch and getting out into the road, was such as anyone who chanced to pass by might readily observe. I sought to ascertain through what progressive steps this outcome was reached. The point here is that observation on one occasion only, no matter how careful and exact that observation may be, does not suffice for the interpretation of this or that instance of animal behavior. Romanes' procedures for collecting anecdotes Romanes' Psychological Criteria for Mind Edward Thorndike's criticisms of Romanes' anecdotal methodology Charles Darwin on mental continuity between humans and animals

|

|

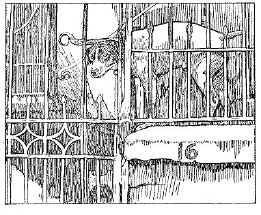

gate is held to be a

latch, but swings open by its own weight if the latch be lifted. Whenever he wanted to go out the fox terrier raised the latch with

the back of his head, and thus released the gate, which swung open. Now the question in

any such case is: How did he learn the trick? In this particular case the question can be

answered, because he was carefully watched. When he was put outside the door, he naturally

wanted to go out into the road, where there was much to tempt him – the chance of a

run, other dogs to sniff at, possibly cats to be worried. He gazed eagerly out through the

railings in the low parapet wall shown in the illustration [A.B. 145, Fig. 21]; and in due

time chanced to gaze out under the latch, lifting it with his head. He withdrew his head

and looked out elsewhere; but the gate had swung open. Here was a fortunate occurrence

arising out of natural tendencies of a dog. But the association between looking out just

there and the open gate with a free passage into the road is somewhat indirect. The

coalescence of mental processes in a conscious situation effective for the guidance of

behavior did not spring into being at once. Only after some ten or twelve experiences, in

each of which the exit was more rapidly made, with less gazing out at wrong places, had

the fox terrier learnt to go straight and without hesitation to the right spot. In this

case the lifting of the latch was unquestionably hit on by accident, and the trick was

only rendered habitual by repeated association in the same situation of the chance act and

the happy escape. Once firmly established, however, the behavior remained constant

throughout the remainder of the dogs life, some five or six years. And, I may add, I could

not succeed, not withstanding much expenditure of biscuits, in teaching him to lift the

latch more elegantly with his muzzle instead of the back of his head.

gate is held to be a

latch, but swings open by its own weight if the latch be lifted. Whenever he wanted to go out the fox terrier raised the latch with

the back of his head, and thus released the gate, which swung open. Now the question in

any such case is: How did he learn the trick? In this particular case the question can be

answered, because he was carefully watched. When he was put outside the door, he naturally

wanted to go out into the road, where there was much to tempt him – the chance of a

run, other dogs to sniff at, possibly cats to be worried. He gazed eagerly out through the

railings in the low parapet wall shown in the illustration [A.B. 145, Fig. 21]; and in due

time chanced to gaze out under the latch, lifting it with his head. He withdrew his head

and looked out elsewhere; but the gate had swung open. Here was a fortunate occurrence

arising out of natural tendencies of a dog. But the association between looking out just

there and the open gate with a free passage into the road is somewhat indirect. The

coalescence of mental processes in a conscious situation effective for the guidance of

behavior did not spring into being at once. Only after some ten or twelve experiences, in

each of which the exit was more rapidly made, with less gazing out at wrong places, had

the fox terrier learnt to go straight and without hesitation to the right spot. In this

case the lifting of the latch was unquestionably hit on by accident, and the trick was

only rendered habitual by repeated association in the same situation of the chance act and

the happy escape. Once firmly established, however, the behavior remained constant

throughout the remainder of the dogs life, some five or six years. And, I may add, I could

not succeed, not withstanding much expenditure of biscuits, in teaching him to lift the

latch more elegantly with his muzzle instead of the back of his head.